First of all, we need to talk about red, because it’s the color that comes to the forefront in Stamps, the series of works that make up Heleno Bernardi’s Rumors exhibition. The first color in the history of art dyed the walls of caves and later metamorphosed into fire and blood in the many odysseys of the image. From the ways in which these two main semantic groups have been represented, red has been the flame of flags, wars and revolutions, and also the river that flows in ravishing passions, in the cloak of princesses, in the curtains of drama, on the carpets of fame.

A stream that flows from life to death, and at the same time reaffirms cycles like rebirths that crackle, like a burning body, in the heart of the ashes of each end.

Red that rekindles beginnings. From voluptuousness, from a state of attention. The red of overflows, coming from a Dionysus on a glass tablet panel in Italy; coming from a medieval Satan that we have learned to re-signify as the opponent of common sense, as the painful and timely challenge.

The fortunately ambiguous connection between the gesture of stamping and the trajectory of this restless artist, who has taken advantage of the notions of accumulation, opacity and form to conceive his works, his creatures, comes from red. These are dives for later.

For now, I remain bathed in crimson, remembering that “color is the touch of the eye, the music of the deaf, the word that comes from the darkness”, as Vermelho himself taught us, transformed into a character and narrator in My Name is Vermelho, by Turkish writer Orhan Pamuk. One of the plot’s narrators, the color speaks of itself: “I’m not afraid of colors or shadows; even less of crowds or loneliness,” it says. And he continues: “Look at me: it’s good to live. Look how good it is to see! To live is to see.

Yes, to live is to see and see again. And art can be a human testimony to the wonder of life. In red, a synthesis of inflammation and bloodletting – the beauty of life also lies in states of transition, in the movement of alchemy. In red, the one who doesn’t fear “the crowd or solitude”, a state of turbulence and attention that anticipates the company of the other. Red as a mirror of the desire for change through encounter and dialog, of the surface that can be a whip and a vulva, a fleshy mirror saying “come”.

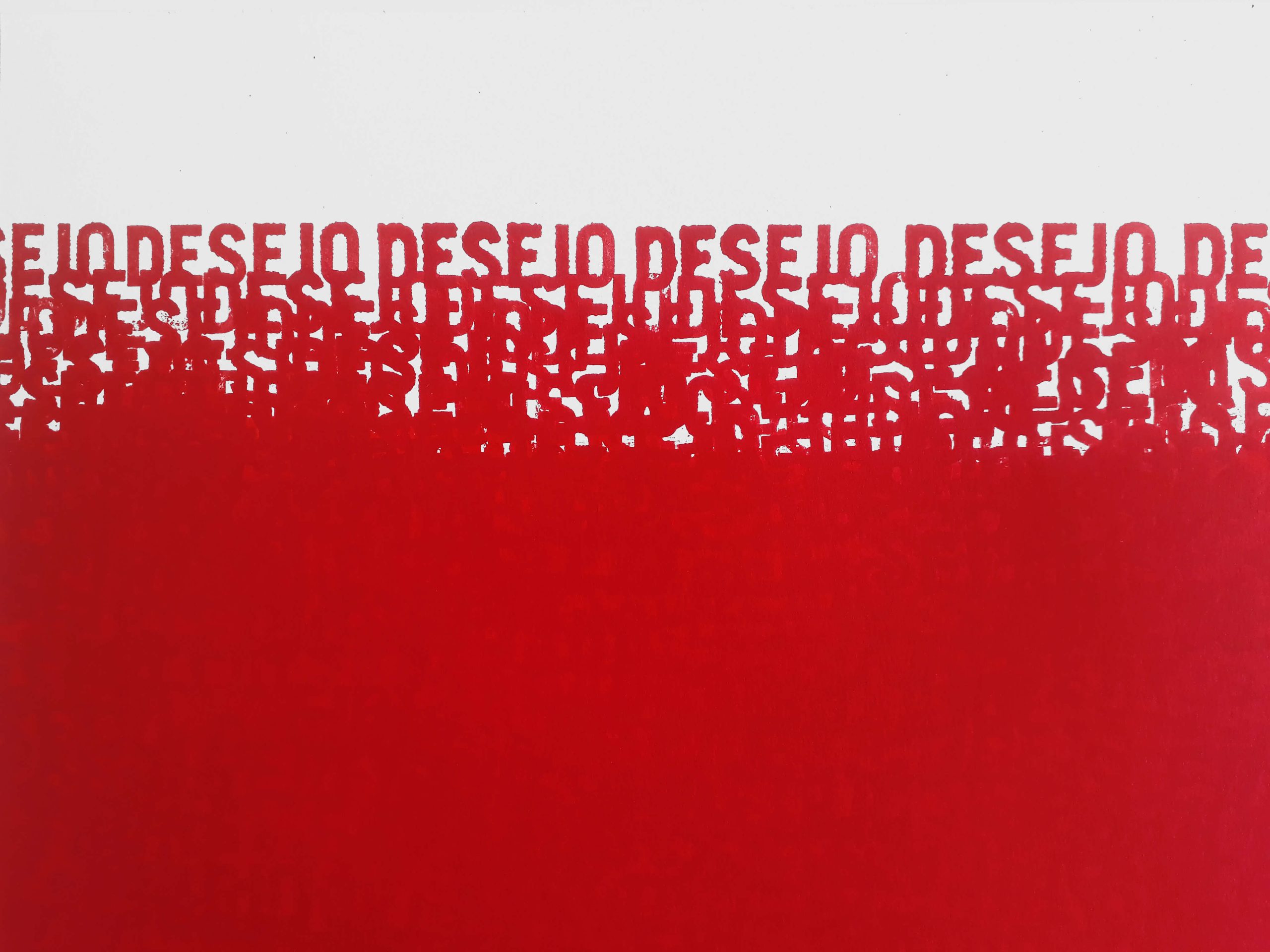

I don’t choose the verb “say” in vain. The red is a kind of scream amidst the repetitions of the stamps on the surface of the paper, whispers that insistently infiltrate the white membrane. Its marks are like a surrounding sound that cannot be drowned out, a murmur that becomes audible and adds new layers of meaning and memory to the current definitions of each word.

Foucault stitched together many eras by thinking of words and things as a game of mirrors similar to the one that takes place in Velasquez’s The Girls. Representation as a mismatched coincidence, as the impossibility of an exact, perfect verisimilitude. Between this and that there is always a lapse, a hiccup, a sphinx-like enigma that devours and wants to be devoured, a seeing to be seen that is evidenced by the couple of monarchs present only as a reflection, what is outside the frame – of writing, of speech – appearing in the narrative or imagetic discourse as an obligatorily fictional ghost of the world.

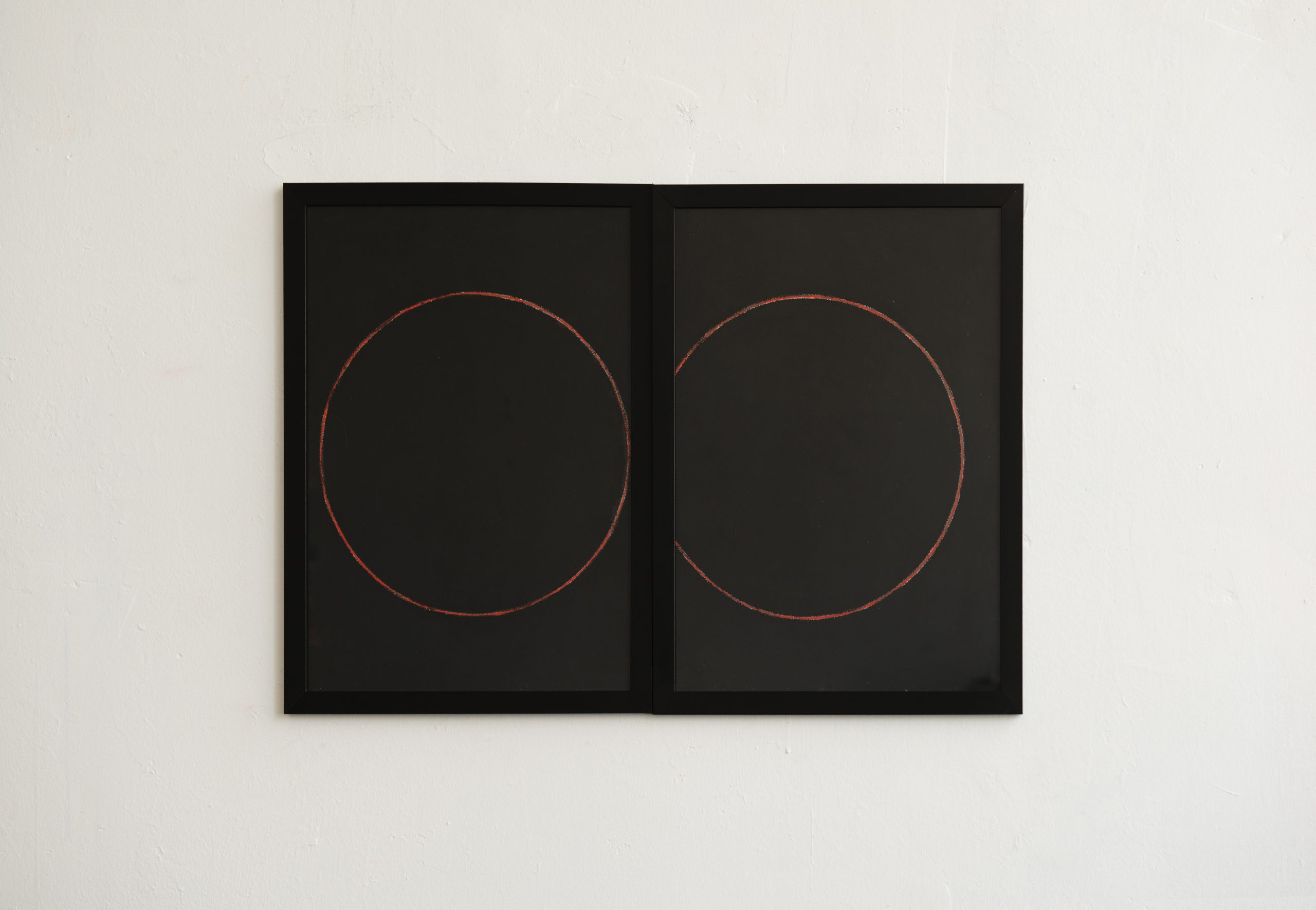

This is what happens with Bernardi’s stamps, in which he rotates a red quadrilateral on a sheet of paper, obtaining a shape. This is then filled in with the same word stamped over and over again. Stamping is in itself a gesture that points to transference and also to a certain allegory. I explain: the stamped ink, by expressing the material body of the stamp as a reverse and engraving, is still a body in the place of another.

Throughout the history of contemporary art, the stamp has been an important means of expression for thinking about representation and promoting friction between medium and message, between the support of an artistic object and its discursive voltage. In the field of Brazilian art alone, this is evident not only in so-called postal art, with the contribution of names such as Sonia Andrade or Paulo Bruscky; if we think about some works from the 1960s and 1970s, such as those by Cildo Meireles, Thereza Simões and Paiva Brasil, we can see that the stamp was a way of covering things in the world with a semantic web shaped by the repetition of gestures and words.

“Who killed Herzog?”, Cildo asked countless times. The insistence on the question, in the midst of the dictatorship, indicated the subversion of the official version of the journalist’s suicide in the torture cellars of São Paulo. Thereza and Paiva, on the other hand, used the stamp to cover walls and architecture with the nebula formed by repeated words – an anticipation of the meaning of “tag cloud”, which would only be known after the advent of the internet – and also constitute an approximation of the idea of site-specific with literature, since a fictional voltage ends up coating the architecture.

Observing how Stamps relates to Bernardi’s previous career, in terms of accumulation, is not only natural, but also points to the maturity of his work. This excess present in the red scream, emulated by the repetition of stamping, appears very strongly in previous works – such as the golden glitter that covered a huge room in Cassino da Urca, in Cassino, or the repetition of the same body shape, suggested as infinite, in the mattresses of While I speak, the hours pass.

Accumulation is also an important characteristic of his painting, in which the different layers/gestures on the surface establish an internal dialog, in which a new attack on the canvas often reinvents and contradicts the grid proposed before.

In Stamps, the perception of accumulation appears in two overlapping ways, making this series a unique contribution to a possible genealogy of this type of engraving or transfer in the recent history of Brazilian art. On one of the paths, we see the gesture repeated in a continuum, as if it could never end, generating that rumor of words I’ve been referring to so much. On the other, there is the materiality of the word itself, produced with the ink, and the way in which this print is superimposed on others, creating a network of words that marks and braids the surface of the paper, and then dissolves into a large area of red monochrome.

In some works, there is a noise coming from the edges that makes the name glimpse. This is the case with “Atlântico” – a red sea, a tomb of lives, a road of looting and loss. In this, a possible synthesis for the very process of violence that exists in all languages: when a language agglomerates, it is because it has murdered many others. In the case of the Portuguese spoken in Brazil, the trail of genocides of bodies and cultures necessarily passes through the Atlantic, where those who brought the silence of the hundreds of original languages arrived; where those who were forced to forget their language and their name to work in the fields and build Brazil came from. As with the language, Bernardi’s works often carry scraps of what has been filled in by red ink – ghosts of dormant words, echoes of other languages.

There is another important point in Stamps, not only in terms of a conversation Bernardi establishes with himself as an artist, but also in terms of a bridge established with a Brazilian neoconstructive legacy. It is not gratuitous that he chooses to quote Ninho, Ovo and Bicho – Hélio Oiticica, Lygia Pape and Lygia Clark, respectively – in works that represent banners instead of paper, fluttering as a sign of what this project cherishes as a gestation.

It is true that the red quadrilateral that rotates modularly on the surface of the paper, like a sundial, points to our geometric identity. An affiliation that goes far beyond neoconcretism, touching on the ancestral geometry of our native peoples (stamping as body painting) and the many African nations that made us up (geometry as a fine print, as a narrative code on fabrics). It is true that the idea of visual poetry – and of a rumor of the things of the world covering painting and drawing, at the same time as it dyes walls and books – also links Bernardi’s work to this moment in our recent art history. But there are less obvious and very strong bridges.

I used the word “rumor”, seen in a multiplied form in the title of the exhibition, also because it gives an account of an indistinct but present sound broth. Jeanne Marie Gagnebin recalls how, in all odysseys, writing is a way of remembering and therefore giving life; and writing is a death sentence – each word like the tomb of what is no more. Oiticica, Pape and Clark turn geometry into a nest, an egg and a bug, transforming Mondrian into an organic body – a form that pulses and breathes. Bernardi, for his part, reaffirms word, color and form as frontiers of the formless, a poem of noise and edges.

If in Apology for Socrates, one of his previous works, the artist dissolved the philosopher’s head – the mother of all heads of this invention we call the West – in soap suds, now he creates a tombstone and horizon for everything that can be shouted in red and whispered insistently and repeatedly through the stamps, until the multiplication of the gesture dissolves and reinvents meanings. In blood and fire, flow and flag, the cycles of the world’s prose, bathed in the voids and silences that come from the edges.