“Movement offers opportunity, recreation, and profit. For others, movement is dangerous and restricted, and its social expulsions are much more severe and permanent.”1

“It is common to think that archaeology studies the past, but this idea is incorrect. Archaeology studies present phenomena: archaeological sites and other types of records that have traveled through time, sometimes for millions of years, to the present day. (…) The past is a foreign country, a strange territory, to which we can never return. Any attempt to reconstruct it will always be speculative, subject to variations in moods, interests, and agendas.”2

Almost ten years ago, the American philosopher Thomas Nail published the book The Figure of the Migrant, in which he theorizes “kinopolitics”, or the politics of movement. This is an innovative perspective on politics, emphasizing the importance of movement, flows, and mobility. Nail challenges traditional conceptions of politics and society, which tend to be analyzed as static, spatial, and temporal, by proposing that movement regimes are fundamental to understanding contemporary transformations. “Societies are always in motion: directing people and objects, reproducing their social conditions (periodicity), and striving to expand their territorial, political, legal, and economic power through various forms of expulsion.”

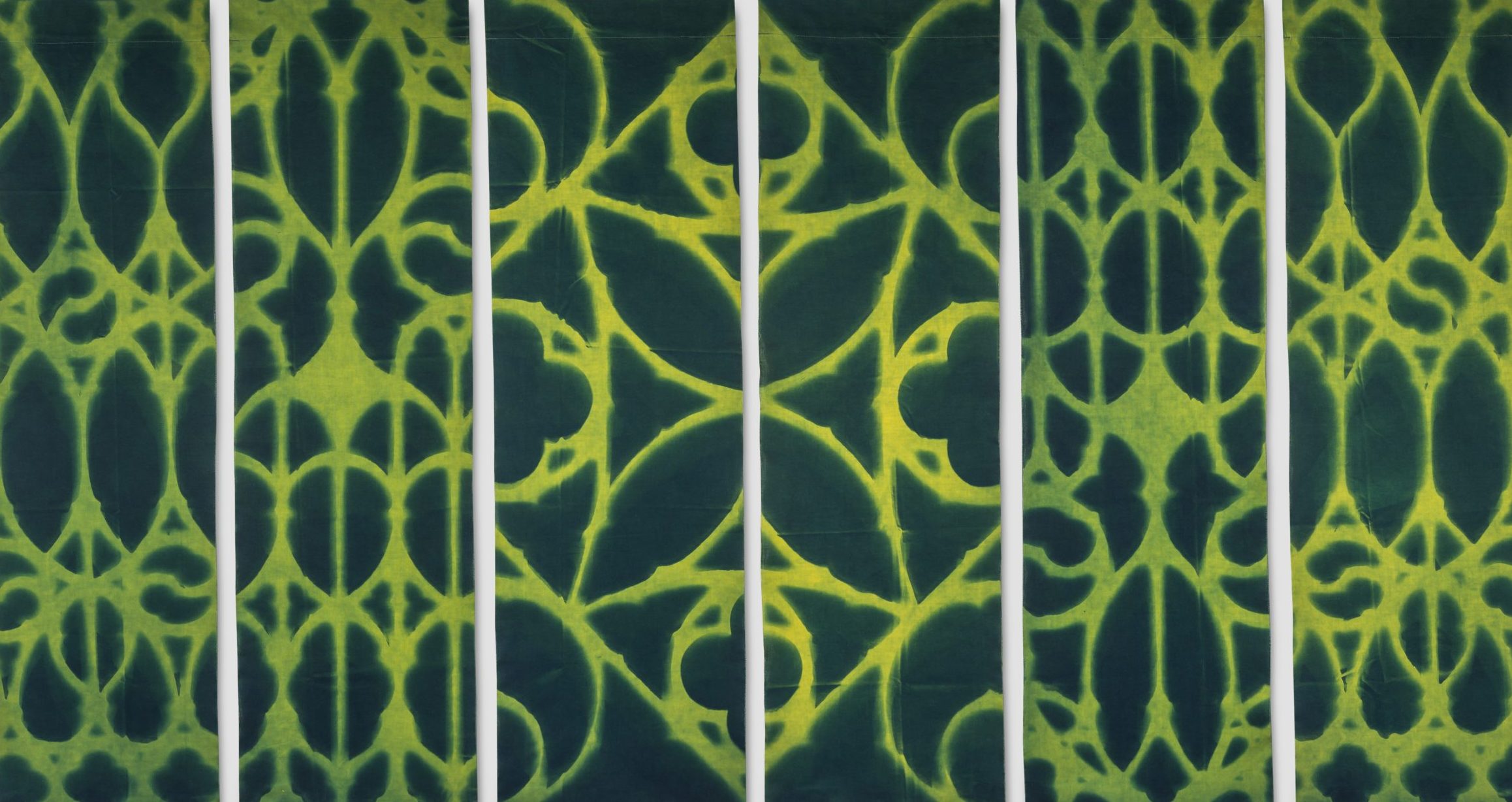

If, in general, this perspective is crucial, it becomes seminal for apprehending a poetics constituted in movement and migration, as is the case with Liene Bosquê. Trained in Visual Arts and Architecture in São Paulo, her career has been built abroad. First, Lisbon, then Chicago, New York, and, more recently, Miami. Bringing her dual education in her baggage, the artist begins to recognize new territories and translate them into her works through the external architecture of built heritage, with railings and fences being very recurrent elements. These elements are found at the eye level of passersby and have the ambiguous function of protecting bodies and restricting movement. Both elements are mostly made of iron, a material that became popular in 19th-century architecture due to the Industrial Revolution and has Paris as the epitome of iron architecture.

Given both the architectural character and the mobility of the passerby, we cannot fail to associate these issues with modernity and Walter Benjamin’s flâneur, a representative figure of a new form of sensory and perceptual experience, mediated by the urban environment and the commodification of society. Although the French capital is not part of Liene Bosquê’s life journey, the influence of Paris in the aesthetics and the imagination of fin de siècle modernity echoes in the cities where she lived, whether Lisbon or São Paulo, a Brazilian metropolis that embodies and represents the economic and social transformations of the 20th century.

Hegemonic aesthetics are migratory in the peripheries of the world. Therefore, the theories of Thomas Nail and Walter Benjamin complement each other in this approach to the politics of movement and aesthetics. While Nail focuses on mobility as a central ontological and political condition for examining and understanding power structures, Benjamin concentrates on the aesthetic and perceptual experience of mobility within the urban context. The flâneur is a local person but unattached to the space, and the migrant (emigrant to the homeland and immigrant to the destination land) is a kind of Möbius strip, belonging and not belonging to the place. In both situations, the constant transformation of society and the city is found.

The works Carandiru and Clarabóias, made in 2003, foreshadow the newly graduated artist’s interest in iron structures even before migration. In the engravings, we have the old prison almost abstracted by its bars, and in the photograms, the structure that lets light into the Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil building in Rio de Janeiro is repeated and superimposed. Both works are based on analog photos taken by her, which are transmuted into other methods of creating images. Here we have the duality pointed out by Nail in his politics of movement: one structure restricts the freedom to come and go, while the other provides beauty and well-being for leisure and culture.

In the other works selected for this exhibition, railings and fences are vestiges of Liene Bosquê’s exploration of the cities where she lived. In some works, techniques of fabric engraving involving photochemical processes like cyanotype and gum bichromate and the alteration of ferrous or ferric compounds, such as oxidation, are used; in others, the shapes are also cut in fabrics, leather, and vinyl. A third strand preserves the memory of places molded in paper and clay. All these series are made directly on-site and carry the characteristic of being portable, easily migrating. Historically, textile art carries a strong load of cultural and affective resistance, becoming, therefore, in the artist’s poetics, a catalyst for both individual and collective memories. In addition to presenting a strong relationship between the body and architecture as reminiscences of places, the fabric works are activated by the movement of exhibition visitors. In contrast to the fluidity of the fabrics are the architectural elements and their fixity. Fences and railings are like boundary territories, membranes that interconnect inside and outside.

In this almost archaeological methodology of Liene, her works resemble urban fossils, a kind of phantasmagoria of forms. Originally referring to a type of illusionist spectacle that emerged in the late 18th century, where images were projected with optical devices to appear real, the term “phantasmagoria” was used by Benjamin to describe the process by which capitalist products and urban spaces are presented in a way that disguises their origins and conditions of production. In contemporary times, these architectural vestiges that often symbolized progress account not only for the illusions of technological optimism and consumption but also for the harsh and hidden social and economic realities of modernity.

In Migrant Archaeologies, the cut-out shapes and some three-dimensional objects also occupy space with their shadows. Presence and absence, positive and negative, light and shadow are interconnected in this kind of new phantasmagoria. The transposition of elements from various places traversed by the artist to the gallery and the way the works embrace the very architecture of the space make us question the history of this space, Barra Funda, and its future.

The more than twenty-year journey of Liene Bosquê is, therefore, told in this exhibition through the lens of the migrating archaeologies she has created. Given that the past is a foreign country, as Eduardo Góes Neves asserts, to which we can never return and being a migrant continues to be the constitutive dimension of social movement over which society is divided, organized, and circulated, her works are glimpses through which we can simultaneously observe the past, present, and future of a world that seems on the verge of disappearing.